Northwest Passage

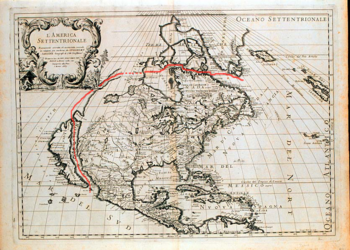

The Northwest Passage is a sea route through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways amidst the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.[1][2] The various islands of the archipelago are separated from one another and the Canadian mainland by a series of Arctic waterways collectively known as the Northwest Passages or Northwestern Passages.[3]

Sought by explorers for centuries as a possible trade route, it was first navigated by Roald Amundsen in 1903–1906. Until 2009, the Arctic pack ice prevented regular marine shipping throughout most of the year, but climate change has reduced the pack ice, and this Arctic shrinkage made the waterways more navigable.[4][5][6][7] However, the contested sovereignty claims over the waters may complicate future shipping through the region: The Canadian government considers the Northwestern Passages part of Canadian Internal Waters,[8] but various countries maintain they are an international strait or transit passage, allowing free and unencumbered passage.[9][10]

Contents |

Overview

Before the Little Ice Age, Norwegian Vikings sailed as far north and west as Ellesmere Island, Skraeling Island and Ruin Island for hunting expeditions and trading with the Inuit groups who already inhabited the region.[11] Between the end of the 15th century and the 20th century, colonial powers from Europe dispatched explorers in an attempt to discover a commercial sea route north and west around North America. The Northwest Passage represented a new route to the established trading nations of Asia, as in 1493 to defuse trade disputes, Pope Alexander VI split the discovered world in two between Spain and Portugal; thus France, the Netherlands, and England were left without a sea route to Asia, either via Africa or South America,[12] unless their ships defied the ban and explored such waters regardless; which they did, and the ban became unenforceable. England called the hypothetical northern route the "Northwest Passage". The desire to establish such a route motivated much of the European exploration of both coasts of North America. When it became apparent that there was no route through the heart of the continent, attention turned to the possibility of a passage through northern waters. This was driven in some part by scientific naiveté, namely an early belief that seawater was incapable of freezing (as late as the mid 18th century, Captain James Cook had reported, for example, that Antarctic icebergs had yielded fresh water, seemingly confirming the hypothesis), and that a route close to the North Pole must therefore exist.[12] The belief that a route lay to the far north persisted for several centuries and led to numerous expeditions into the Arctic, including the attempt by Sir John Franklin in 1845. In 1906, Roald Amundsen first successfully completed a path from Greenland to Alaska in the sloop Gjøa.[13] Since that date, several fortified ships have made the journey.

From west to east the Northwest Passage runs through the Bering Strait (separating Russia and Alaska), Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, and then through several waterways that go through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. There are five to seven routes through the archipelago, including the McClure Strait, Dease Strait, and the Prince of Wales Strait, but not all of them are suitable for larger ships.[9][14] The passage then goes through Baffin Bay and the Davis Strait into the Atlantic Ocean.

There has been speculation that with the advent of global warming the passage may become clear enough of ice to again permit safe commercial shipping for at least part of the year. On August 21, 2007, the Northwest Passage became open to ships without the need of an icebreaker. According to Nalan Koc of the Norwegian Polar Institute this is the first time it has been clear since they began keeping records in 1972.[4][15] The Northwest Passage opened again on August 25, 2008.[16]

Thawing ocean or melting ice simultaneously opened up the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route (Northeast Passage), making it possible to sail around the Arctic ice cap.[17] Compared to 1979, Daily Mail published "Blocked: The Arctic ice, showing as a pink mass in the 1979 picture, links up with northern Canada and Russia."[18] Awaited by shipping companies, this 'historic event' will cut thousands of miles off their routes. Warning, however, that the NASA satellite images indicated the Arctic may have entered a "death spiral" caused by global warming, Professor Mark Serreze, a sea ice specialist at National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), USA, said: "The passages are open. It's a historic event. We are going to see this more and more as the years go by."[19][20] Due to Arctic shrinkage, the Beluga group of Bremen, Germany, sent the first Western commercial vessels through the Northern Sea Route (Northeast Passage) in 2009.[21] However, Canada's Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that "ships entering the North-West passage should first report to his government."[22]

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Northwestern Passages as follows:[23]

On the West. The Eastern limit of Beaufort Sea [From Lands End through the Southwest coast of Prince Patrick Island to Griffiths Point, thence a line to Cape Prince Alfred, the Northwestern extreme of Banks Island, through its West coast to Cape Kellet, the Southwestern point, and thence a line to Cape Bathurst on the mainland ()].

On the Northwest. The Arctic Ocean between Lands End, Prince Patrick Island, and C. Columbia, Ellesmere Island.

On the Northeast. The Coast of Ellesmere Island between C. Columbia and C. Sheridan the Northern limit of Baffin Bay.

On the East. The East Coast of Ellesmere Island between C. Sheridan and Cape Norton Shaw (), thence across to Phillips Point (Coburg Island) through this Island to Marina Peninsula () and across to Cape Fitz Roy (Devon Island) down the East Coast to Cape Sherard (Cape Osborn) () and across to Cape Liverpool, Bylot Island (); down the East coast of this island to Cape Graham Moore, its southeastern point, and thence across to Cape Macculloch () and down the East coast of Baffin Island to East Bluff, its Southeastern extremity, and thence the Eastern limit of Hudson Strait.

On the South. The mainland coast of Hudson Strait; the Northern limits of Hudson Bay; the mainland coast from Beach Point to Cape Bathurst.

Historical expeditions

As a result of their westward explorations and their settlement of Greenland, the Vikings sailed as far north and west as Ellesmere Island, Skraeling Island and Ruin Island for hunting expeditions and trading with Inuit groups. The subsequent arrival of the Little Ice Age is thought to be one of the reasons that further European seafaring into the Northwest Passage ceased until the late 15th century.

Strait of Anián

In 1539, Hernán Cortés commissioned Francisco de Ulloa to sail along the peninsula of Baja California on the western coast of America. Ulloa concluded that the Gulf of California was the southernmost section of a strait supposedly linking the Pacific with the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. His voyage perpetuated the notion of the Island of California and saw the beginning of a search for the Strait of Anián.

The strait probably took its name from Ania, a Chinese province mentioned in a 1559 edition of Marco Polo's book; it first appears on a map issued by Italian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi about 1562. Five years later Bolognini Zaltieri issued a map showing a narrow and crooked Strait of Anian separating Asia from the Americas. The strait grew in European imagination as an easy sea lane linking Europe with the residence of Khagan (the Great Khan) in Cathay (northern China). It was originally placed at approximately the latitude of San Diego, California, leading some who live in the region to call it "Anian" or "Aniane".

Cartographers and seamen tried to demonstrate its reality. Sir Francis Drake sought the western entrance in 1579. The Greek pilot Juan de Fuca, sailing under the Portuguese flag, claimed he had sailed the strait from the Pacific to the North Sea and back in 1592. The Spaniard Bartholomew de Fonte claimed to have sailed from Hudson Bay to the Pacific via the strait in 1640.

Northern Atlantic

The first recorded attempt to discover the Northwest Passage was the east-west voyage of John Cabot in 1497, sent by Henry VII in search of a direct route to the Orient.[12] The next of several British expeditions was launched in 1576 by Martin Frobisher, who took three trips west to what is now the Canadian Arctic in order to find the passage. Frobisher Bay, which he first charted, is named after him. As part of another hunt, in July 1583 Sir Humphrey Gilbert, who had written a treatise on the discovery of the passage and was a backer of Frobisher, claimed the territory of Newfoundland for the English crown. On August 8, 1585, the English explorer John Davis entered Cumberland Sound, Baffin Island for the first time.

The major rivers on the east coast were also explored in case they could lead to a transcontinental passage. Jacques Cartier's explorations of the Saint Lawrence River were initiated in hope of finding a way through the continent. Indeed, Cartier managed to convince himself that the St. Lawrence was the Passage; when he found the way blocked by rapids at what is now Montreal, he was so certain that these rapids were all that was keeping him from China (in French, la Chine), that he named the rapids for China. To this day, they are the Lachine Rapids. In 1609 Henry Hudson sailed up what is now called the Hudson River in search of the Passage; encouraged by the saltiness of the water, he reached present-day Albany, New York, before giving up. He later explored the Arctic and Hudson Bay. In 1611, while in James Bay, Hudson's crew mutinied. He and his teenage son John, along with seven sick, infirm, or loyal crewmen, were set adrift in a small open boat. He was never seen again.[24][25] Cree oral legend reports that the survivors lived and traveled with the Cree for more than a year.

René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle built the sailing ship, Le Griffon, in his quest to find the Northwest Passage in the upper Great Lakes. Le Griffon disappeared in 1679 on the return trip of her maiden voyage.[26] In the spring of 1682, La Salle made his famous voyage down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. La Salle led an expedition from France in 1684 to establish a French colony on the Gulf of Mexico. He was murdered by his followers in 1687.[27]

Northern Pacific

Although most Northwest Passage expeditions originated in Europe or on the east coast of North America and sought to traverse the Passage in the westbound direction, some progress was made in exploration of its western end as well.

In 1728 Vitus Bering, a Danish Navy officer in Russian service, used the strait first discovered by Semyon Dezhnyov in 1648 but later accredited to and named after Bering (the Bering Strait), concluding North America and Russia were separate land masses.

In 1741 with Lieutenant Aleksei Chirikov he went in search of further lands beyond Siberia. While separated, Chirikov discovered several of the Aleutian Islands while Bering charted the Alaskan region before the scurvy-ravaged ship wrecked off the Kamchatka Peninsula.

In 1762, the English trading ship Octavius reportedly hazarded the passage from the west but became trapped in sea ice.

In 1775, the whaler Herald found the Octavius adrift near Greenland with the bodies of her crew frozen below decks. Thus the Octavius may have earned the distinction of being the first Western sailing ship to make the passage, although the fact that it took 13 years and occurred after the crew was dead somewhat tarnishes this achievement. (The veracity of the Octavius story is questionable.)

The Spanish made numerous voyages to the northwest coast of North America during the late 18th century. Determining whether a North West Passage existed was one of the motivations for this effort. Among the voyages that involved careful searches for a Passage include the 1775 and 1779 voyages of Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. The journal of Francisco Antonio Mourelle, who served as Quadra's second in command in 1775, fell into English hands and was translated and published in London. Captain James Cook made use of the journal during his explorations of the region. In 1791 Alessandro Malaspina sailed to Yakutat Bay, Alaska, which was rumoured to be a Passage. In 1790 and 1791 Francisco de Eliza led several exploring voyages into the Strait of Juan de Fuca, searching for a possible North West Passage and finding the Strait of Georgia. To fully explore this new inland sea an expedition under Dionisio Alcalá Galiano was sent in 1792. He was explicitly ordered to explore all channels that might turn out to be a North West Passage.

Cook and Vancouver

In 1776 Captain James Cook was dispatched by the Admiralty in Great Britain under orders driven by a 1745 act which, when extended in 1775, promised a £20,000 prize for whoever discovered the passage. Initially the Admiralty had wanted Charles Clerke to lead the expedition, with Cook (in retirement following his exploits in the Pacific) acting as a consultant. However Cook had researched Bering's expeditions, and the Admiralty ultimately placed their faith in the veteran explorer to lead with Clerke accompanying him.

After journeying through the Pacific, in another west–east attempt, Cook began at Nootka Sound in April 1777, and headed north along the coastline, charting the lands and searching for the regions sailed by the Russians 40 years previously. The Admiralty's orders had commanded the expedition to ignore all inlets and rivers until they reached a latitude of 65°N. Cook, however, failed to make any progress in sighting a Northwestern Passage.

Various officers on the expedition, including William Bligh, George Vancouver, and John Gore, thought the existence of a route was 'improbable'. Before reaching 65°N they found the coastline pushing them further south, but Gore convinced Cook to sail on into the Cook Inlet in the hope of finding the route. They continued to the limits of the Alaskan peninsula and the start of the 1,200 mi (1,900 km) chain of Aleutian Islands. Despite reaching 70°N they encountered nothing but icebergs.[12]

From 1791 to 1795, the Vancouver Expedition (led by George Vancouver who had accompanied Cook previously) surveyed in detail all the passages from the Northwest Coast and confirmed that there was no such passage south of the Bering Strait.[28] This conclusion was supported by the evidence of Alexander MacKenzie who explored the Arctic and Pacific oceans in 1793.

19th century

In the first half of the 19th century, some parts of the actual Northwest Passage (north of the Bering Strait) were explored separately by many expeditions, including those by John Ross, William Edward Parry, and James Clark Ross; overland expeditions were also led by John Franklin, George Back, Peter Warren Dease, Thomas Simpson, and John Rae. In 1825 Frederick William Beechey explored the north coast of Alaska, discovering Point Barrow.

Sir Robert McClure was credited with the discovery of the real Northwest Passage in 1851 when he looked across McClure Strait from Banks Island and viewed Melville Island. However, this strait was not navigable to ships at that time, and the only usable route linking the entrances of Lancaster Sound and Dolphin and Union Strait was discovered by John Rae in 1854.

Franklin expedition

In 1845 a lavishly equipped two-ship expedition led by Sir John Franklin sailed to the Canadian Arctic to chart the last unknown swaths of the Northwest Passage. Confidence was high, given there was less than 500 km (310 mi) of unexplored Arctic mainland coast by then. When the ships failed to return, relief expeditions and search parties explored the Canadian Arctic, which resulted in a thorough charting of the region along with a possible passage. Many artifacts from the expedition were found over the next century and a half, including notes that the ships were ice-locked in 1846 near King William Island, about half way through the passage, unable to break free. Franklin died in 1847 and Captain Francis Rawdon Moira Crozier took over command. In 1848 the expedition abandoned ships and tried to escape south across the tundra by sledge. Although some of the crew may not have died until the early 1850s, no evidence has ever been found of any survivors. In 1853 John Rae received information from local Inuit about the fate of Franklin's expedition, but his reports were not welcomed.

Starvation, exposure and scurvy all contributed to the deaths. In 1981 Owen Beattie, an anthropologist from the University of Alberta, examined remains from sites associated with the expedition.[29] This led to further investigations and the examination of tissue and bone from the frozen bodies of three seamen, John Torrington, William Braine and John Hartnell, exhumed from the permafrost of Beechey Island. Laboratory tests revealed high concentrations of lead in all three (the expedition carried 8,000 tins of food sealed with a lead-based solder).[30] Another researcher has suggested botulism caused deaths among crew members.[31] New evidence, confirming reports first made by John Rae in 1854 based on Inuit accounts, has shown cannibalism was a last resort for some of the crew.[32]

McClure expedition

During the search for Franklin, Commander Robert McClure and his crew in HMS Investigator traversed the Northwest Passage from west to east in the years 1850 to 1854, partly by ship and partly by sledge. McClure started out from England in December 1849, sailed the Atlantic Ocean south to Cape Horn and entered the Pacific Ocean. He sailed the Pacific north and passed through the Bering Strait, turning east at that point and reaching Banks Island.

McClure's ship was trapped in the ice for three winters near Banks Island, at the western end of Viscount Melville Sound. Finally McClure and his crew—who were by that time dying of starvation—were found by searchers who had travelled by sledge over the ice from a ship of Sir Edward Belcher's expedition, and returned with them to Belcher's ships, which had entered the sound from the east. On one of Belcher's ships, McClure and his crew returned to England in 1854, becoming the first people to circumnavigate the Americas and to discover and transit the Northwest Passage, albeit by ship and by sledge over the ice. (Both McClure and his ship were found by a party from HMS Resolute, one of Belcher's ships, so his sledge journey was relatively short.[33]) This was an astonishing feat for that day and age, and McClure was knighted and promoted in rank. (He was made rear-admiral in 1867.) Both he and his crew also shared £10,000 awarded them by the British Parliament. In July 2010 Canadian archaeologists found the HMS "Investigator" fairly intact but sunk about 8m below the surface. [34]

John Rae

The expeditions by Franklin and McClure were in the tradition of British exploration: well-funded ship-borne expeditions using modern technology, and usually including British Naval personnel. By contrast, John Rae was an employee of the Hudson's Bay Company, which was the major driving force behind exploration of the Canadian North. They adopted a pragmatic approach and tended to be land-based. While Franklin and McClure attempted to explore the passage by sea, Rae explored by land, using dog sleds and employing techniques he learned from the native Inuit. The Franklin and McClure expeditions each employed hundreds of personnel and multiple ships. John Rae's expeditions included less than ten people and succeeded. Rae was also the explorer with the best safety record, having lost only one man in years of traversing Arctic lands. In 1854,[35] Rae returned with information about the outcome of the ill-fated Franklin expedition.

Amundsen expedition

The Northwest Passage was not conquered by sea until 1906, when the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who had sailed just in time to escape creditors seeking to stop the expedition, completed a three-year voyage in the converted 47-ton herring boat Gjøa, after three winters trapped in ice. At the end of this trip, he walked into the city of Eagle, Alaska, and sent a telegram announcing his success. Although his chosen east–west route, via the Rae Strait, contained young ice and thus was navigable, some of the waterways were extremely shallow (3 feet, or 1 meter, deep) making the route commercially impractical.

Later expeditions

The first traversal of the Northwest Passage via dog sled[36] was accomplished by Greenlander Knud Rasmussen while on the Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–1924). Rasmussen, and two Greenland Inuit, travelled from the Atlantic to the Pacific over the course of 16 months via dog sled.

In 1940, Canadian RCMP officer Henry Larsen was the second to sail the passage, crossing west to east, from Vancouver to Halifax. More than once on this trip, it was unknown whether the St. Roch a Royal Canadian Mounted Police "ice-fortified" schooner would survive the ravages of the sea ice. At one point, Larsen wondered "if we had come this far only to be crushed like a nut on a shoal and then buried by the ice." The ship and all but one of her crew survived the winter on Boothia Peninsula. Each of the men on the trip was awarded a medal by Canada's sovereign, King George VI, in recognition of this notable feat of Arctic navigation.

Later in 1944, Larsen's return trip was far more swift than his first; the 28 months he took on his first trip was significantly reduced, and he took 86 days to sail back from Halifax, Nova Scotia to Vancouver, British Columbia,[37] setting the mark for having traversed it in a single season. The ship followed a more northerly partially uncharted route, and it also had extensive upgrades.

On July 1, 1957, the United States Coast Guard cutter Storis departed in company with U.S. Coast Guard cutters Bramble (WLB-392) and SPAR (WLB-403) to search for a deep draft channel through the Arctic Ocean and to collect hydrographic information. Upon her return to Greenland waters, the Storis became the first U.S.-registered vessel to circumnavigate North America. Shortly after her return in late 1957, she was reassigned to her new home port of Kodiak, Alaska.

In 1969, the SS Manhattan made the passage, accompanied by the Canadian icebreaker Sir John A. Macdonald. The Manhattan was a specially reinforced supertanker sent to test the viability of the passage for the transport of oil. While the Manhattan succeeded, the route was deemed not to be cost effective, and the Alaska Pipeline was built instead.

In June 1977, sailor Willy de Roos left Belgium to attempt the Northwest Passage in his 13.8 m (45 ft) steel yacht Williwaw. He reached the Bering Strait in September and after a stopover in Victoria, British Columbia, went on to round Cape Horn and sail back to Belgium, thus being the first sailor to circumnavigate the Americas entirely by ship.[38]

In 1984, the commercial passenger vessel MS Explorer (which sank in the Antarctic Ocean in 2007) became the first cruise ship to navigate the Northwest Passage.[39]

In July 1986, Jeff MacInnis and Wade Rowland set out on an 18-foot catamaran called Perception on a 100-day sail, west to east, across the Northwest Passage.[40]link CBC panel discussion. This pair is the first to sail the passage, although they had the benefit of doing so over a couple of summers.

In July 1986, David Scott Cowper set out from England in a 12.8 m (42 ft) lifeboat, the Mabel El Holland, and survived three Arctic winters in the Northwest Passage before reaching the Bering Strait in August 1989. He then continued around the world via the Cape of Good Hope to arrive back on 24 September 1990, becoming the first vessel to circumnavigate the world via the Northwest Passage.[41]

On July 1, 2000, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police patrol vessel Nadon, having assumed the name St Roch II, departed Vancouver on a "Voyage of Rediscovery". Nadon's mission was to circumnavigate North America via the Northwest Passage and the Panama Canal, recreating the epic voyage of her predecessor, St. Roch. The 22,000-mile Voyage of Rediscovery was intended to raise awareness concerning St. Roch and kick off the fund-raising efforts necessary to ensure St. Roch's continued preservation. The voyage was organized by the Vancouver Maritime Museum and supported by a variety of corporate sponsors and agencies of the Canadian government. Nadon is an aluminum, catamaran-hulled, high-speed patrol vessel. To make the voyage possible, she was escorted and supported by the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker Simon Fraser. The Coast Guard vessel was chartered by the Voyage of Rediscovery and crewed by volunteers. Throughout the voyage, she provided a variety of necessary services, including provisions and spares, fuel and water, helicopter facilities, and ice escort; she also conducted oceanographic research during the voyage. The Voyage of Rediscovery was completed in five and a half months, with Nadon arriving back at Vancouver on December 16, 2000.

On September 1, 2001, Northabout, an 14.3 m (47 ft) aluminium sailboat with diesel engine,[42] built and captained by Jarlath Cunnane, completed the Northwest Passage east-to-west from Ireland to the Bering Strait. The voyage from the Atlantic to the Pacific was completed in 24 days. The Northabout then cruised in Canada for two years before it returned to Ireland in 2005 via the Northeast Passage, thereby completing the first east-to-west circumnavigation of the pole by a single sailboat. The Northeast Passage return along the coast of Russia was slower, starting in 2004, with an ice stop and winter over in Khatanga, Siberia—hence the return to Ireland via the Norwegian coast in October 2005. On January 18, 2006, the Cruising Club of America awarded Jarlath Cunnane their Blue Water Medal, an award for "meritorious seamanship and adventure upon the sea displayed by amateur sailors of all nationalities."

On July 18, 2003, a father and son team, Richard and Andrew Wood, with Zoe Birchenough, sailed the yacht Norwegian Blue into the Bering Strait. Two months later she sailed into the Davis Strait to become the first British yacht to transit the Northwest Passage from west to east. She also became the only British vessel to complete the Northwest Passage in one season, as well as the only British sailing yacht to return from there to British waters.[43]

In 2006 a scheduled cruise liner (the MS Bremen) successfully ran the Northwest Passage [1], helped by satellite images telling where sea ice was.

On May 19, 2007, a French sailor, Sébastien Roubinet, and one other crew member left Anchorage, Alaska, in Babouche, a 7.5 m (25 ft) ice catamaran designed to sail on water and slide over ice. The goal was to navigate west to east through the Northwest Passage by sail only. Following a journey of more than 7,200 km (4,474 mi), Roubinet reached Greenland on September 9, 2007, thereby completing the first Northwest Passage voyage made without engine in one season.[44]

International waters dispute

The Canadian government claims that some of the waters of the Northwest Passage, particularly those in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, are internal to Canada, giving Canada the right to bar transit through these waters.[10] Most maritime nations,[45] including the United States and the nations of the European Union,[46] consider them to be an international strait, where foreign vessels have the right of "transit passage".[47] In such a régime, Canada would have the right to enact fishing and environmental regulation, and fiscal and smuggling laws, as well as laws intended for the safety of shipping, but not the right to close the passage.[9][48] In 1985, the U.S. icebreaker Polar Sea passed through from Greenland to Alaska, the ship submitted to inspection by the Canadian Coast Guard before passing through. The United States government, when asked by a Canadian reporter, indicated that they did not legally ask permission as they were not required to. The Canadian government issued a declaration in 1986 reaffirming Canadian rights to the waters. However, the United States refused to recognize the Canadian claim. In 1988 the governments of Canada and the U.S. signed an agreement, "Arctic Cooperation", that resolved the practical issue without solving the sovereignty questions. Under the law of the sea, ships engaged in transit passage are not permitted to engage in research. The agreement states that all US Coast Guard vessels are engaged in research, and so would require permission from the Government of Canada to pass through.[49]

In late 2005, it was alleged that U.S. nuclear submarines had travelled unannounced through Canadian Arctic waters, sparking outrage in Canada. In his first news conference after the 2006 federal election, Prime Minister-designate Stephen Harper contested an earlier statement made by the U.S. ambassador that Arctic waters were international, stating the Canadian government's intention to enforce its sovereignty there. The allegations arose after the U.S. Navy released photographs of the USS Charlotte surfaced at the North Pole.[50][51]

On April 9, 2006, Canada's Joint Task Force North declared that the Canadian military will no longer refer to the region as the Northwest Passage, but as the Canadian Internal Waters.[52] The declaration came after the successful completion of Operation Nunalivut (Inuktitut for "the land is ours"), which was an expedition into the region by five military patrols.[53]

In 2006 a report prepared by the staff of the Parliamentary Information and Research Service of Canada suggested that because of the September 11 attacks the United States might be less interested in pursuing the international waterways claim in the interests of having a more secure North American perimeter.[49] This report was based on an earlier paper, The Northwest Passage Shipping Channel: Is Canada’s Sovereignty Really Floating Away? by Andrea Charron, given to the 2004 Canadian Defence and Foreign Affairs Institute Symposium.[14] Later in 2006 former United States Ambassador to Canada, Paul Cellucci agreed with this position; however, the succeeding ambassador, David Wilkins, stated that the Northwest Passage was in international waters.[54]

On July 9, 2007, Prime Minister Harper announced the establishment of a deep-water port in the far North. In the government press release the Prime Minister is quoted as saying, “Canada has a choice when it comes to defending our sovereignty over the Arctic. We either use it or lose it. And make no mistake, this Government intends to use it. Because Canada’s Arctic is central to our national identity as a northern nation. It is part of our history. And it represents the tremendous potential of our future."[55]

On July 10, 2007, Rear Admiral Timothy McGee of the United States Navy, and Rear Admiral Brian Salerno of the United States Coast Guard announced that the United States would also be increasing its ability to patrol the Arctic.[56]

Effects of climate change

According to the testimony of Viking sagas such as the Saga of Erik the Red and Grœnlendinga saga, from approximately AD 1000 to 1200 (a conservative interval that also happens to include the dates allotted to some of the larger Norse ships), the Arctic appears to have been much warmer than now, as full-fledged farming created a sustainable economy for the Norse and Icelandic settlers of Greenland. This warm period is known as the Medieval Warm Period and just preceded the Little Ice Age which ultimately led to the demise of the Norse colonies in Greenland. This fact, combined with persistent rumours of a Lost Ship of the Desert (in California's Colorado Desert) variously described as a Viking longboat or a Spanish Galleon, has led some to conjecture that the Northwest Passage may have been not only navigable during this period, but indeed explored by Norse explorers.

The sea level in the Arctic during the Medieval Warm period was different from that of the present day.[57] Because of glacial rebound land levels of the land masses about the Northwest Passage have risen upwards of 20 m (66 ft) in the centuries after the Viking times.

In the summer of 2000, several ships took advantage of thinning summer ice cover on the Arctic Ocean to make the crossing. It is thought that global warming is likely to open the passage for increasing periods of time, making it attractive as a major shipping route. However the passage through the Arctic Ocean would require significant investment in escort vessels and staging ports. Therefore the Canadian commercial marine transport industry does not anticipate the route as a viable alternative to the Panama Canal even within the next 10 to 20 years.[58]

On September 14, 2007, the European Space Agency stated that, based on satellite images, ice loss had opened up the passage "for the first time since records began in 1978". According to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, the latter part of the 20th century and the start of the 21st had seen marked shrinkage of ice cover. The extreme loss in 2007 rendered the passage "fully navigable".[4][5] However, the ESA study was based only on analysis of satellite images and could in practice not confirm anything about the actual navigation of the waters of the passage. The ESA suggested the passage would be navigable "during reduced ice cover by multi-year ice pack" (namely sea ice surviving one or more summers) where previously any traverse of the route had to be undertaken during favourable seasonable climatic conditions or by specialist vessels or expeditions. The agency's report speculated that the conditions prevalent in 2007 had shown the passage may "open" sooner than expected.[6] An expedition in May 2008 reported that the passage was not yet continuously navigable even by an icebreaker and not yet ice-free.[59]

Scientists at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union on December 13, 2007, revealed that NASA satellites observing the western Arctic. showed a 16% decrease in cloud coverage during the summer of 2007 compared to 2006. This would have the effect of allowing more sunlight to penetrate Earth's atmosphere and warm the Arctic Ocean waters, thus melting sea ice and contributing to the opening the Northwest Passage.[60]

In recent years at least one scheduled cruise liner (the MS Bremen in 2006) has successfully run the Northwest Passage [2], helped by satellite images telling where sea ice was. In January 2010, the ongoing reduction in the Arctic Sea ice led telecoms cable specialist Kodiak-Kenai Cable to propose the laying of a fibre-optic cable connecting London and Tokyo, by way of the Northwest Passage, saying the proposed system would nearly cut in half the time it takes to send messages from the United Kingdom to Japan.

2008 sealift

On November 28, 2008, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reported that the Canadian Coast Guard confirmed the first commercial ship sailed through the Northwest Passage. In September 2008, the MV Camilla Desgagnés, owned by Desgagnés Transarctik Inc. and, along with the Arctic Cooperative, is part of Nunavut Sealift and Supply Incorporated (NSSI),[61] transported cargo from Montreal to the hamlets of Cambridge Bay, Kugluktuk, Gjoa Haven and Taloyoak. A member of the crew is reported to have claimed that "there was no ice whatsoever". Shipping from the east is to resume in the fall of 2009.[62] Although sealift is an annual feature of the Canadian Arctic this is the first time that the western communities have been serviced from the east. The western portion of the Canadian Arctic is normally supplied by Northern Transportation Company Limited (NTCL) from Hay River. The eastern portion by NNSI and NTCL from Churchill and Montreal.[63][64]

See also

- Territorial claims in the Arctic

- Northern Sea Route

- North West Passage Territorial Park

- Arctic Bridge

- List of Arctic expeditions

- Arctic exploration

Notes

- ↑ "Northwest passage". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. http://m-w.com/dictionary/northwest%20passage.

- ↑ "The Northwest Passage Thawed". http://www.carc.org/whatsnew/writings/amitchell.html.

- ↑ IHO Codes for Oceans & Seas, and Other Code Systems: IHO 23-3rd: Limits of Oceans and Seas, Special Publication 23 (3rd ed.). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. http://ioc.unesco.org/oceanteacher/OceanTeacher2/06_OcDtaMgtProc/01_DataOps/06_OcDtaForm/01_OcDtaFormFunda/01_Codes/PreviousIHOandOther.htm.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Satellites witness lowest Arctic ice coverage in history". http://www.esa.int/esaCP/SEMYTC13J6F_index_0.html. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Warming 'opens Northwest Passage'". BBC News. September 14, 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/6995999.stm. Retrieved 2007-09-14.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 BBC News "Plain Sailing on the Northwest Passage"

- ↑ Keating, Joshua E. (December 2009). "The Top 10 Stories You Missed in 2009: A few ways the world changed while you weren’t looking". Foreign Policy. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2009/11/30/the_top_10_stories_you_missed_in_2009.

- ↑ "TP 14202 E Interpretation". Transport Canada. http://www.tc.gc.ca/marinesafety%5CTP%5CTP14202%5Cinterpretation.htm.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "The Northwest Passage and Climate Change from the Library of Parliament—Canadian Arctic Sovereignty". http://www.parl.gc.ca/information/library/PRBpubs/prb0561-e.htm#Challenges.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Naval Operations in an ice-free Arctic". http://www.natice.noaa.gov/icefree/FinalArcticReport.pdf.

- ↑ Inuit-Norse contact in the Smith Sound region/Schledermann, P. McCullough, K.M.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Collingridge, Vanessa (2002). Captain Cook. Ebury Press. ISBN 0091888980.

- ↑ Mills, William James (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 13. ISBN 1576074226.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Andrea Charron—The Northwest Passage Shipping Channel: Is Canada’s Sovereignty Really Floating Away?PDF (225 KB)

- ↑ Fouché, Gwladys (August 28, 2007). "North-West Passage is now plain sailing". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2007/aug/28/climatechange.internationalnews. Retrieved April 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Arctic shortcuts open up; decline pace steady". http://www.nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/2008/082508.html.

- ↑ Arctic ice cap, 2007

- ↑ Arctic ice cap, 1979

- ↑ ptinews.com, North Pole becomes an 'island'

- ↑ independent.co.uk, For the first time in human history, the North Pole can be circumnavigated

- ↑ {{citation |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/8264345.stm |title=Arctic trail blazers make history |accessdate=2010-08-17

- ↑ telegraph.co.uk, Arctic becomes an island as ice melts

- ↑ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition". International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. http://www.iho-ohi.net/iho_pubs/standard/S-23/S23_1953.pdf. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ↑ Excerpt from A Larger Discourse of the Same Voyage, by Abacuk Pricket, 1625

- ↑ Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ↑ Mansfield, Ed., J.B. (1899, 2003). "History of the Great Lakes: Volume I". Chicago: Maritime History of the Great Lakes; Original: J.H. Beers & Co.. pp. 78–90. http://www.halinet.on.ca/GreatLakes/Documents/HGL/default.asp?ID=c007. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ "Rene-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle". Chronicles of America. http://www.chroniclesofamerica.com/french/lasalle.htm. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ↑ Meany, Edmond Stephen. "Vancouver's discovery of Puget Sound". Mystic Seaport. http://www.mysticseaport.org/library/initiative/ImPage.cfm?PageNum=2&BibId=17506&ChapterId=3. Retrieved April 13, 2007.

- ↑ Arctic paleoradiology: portable radiographic examination of two frozen sailors from the Franklin Expedition (1845–1845) PMID 3300222

- ↑ Bayliss, Richard. "Sir John Franklin's last arctic expedition: a medical disaster. J.R. Soc. Med. 2002:95 151–153". http://www.jrsm.org/cgi/content/full/95/3/151. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ Horowitz BZ: Polar poisons; did Botulism doom the Franklin expedition? PMID 14677794

- ↑ Keenleyside, Anne. "The final days of the Franklin Expedition: new skeletal evidence. Arctic 50:(1) 36-36 (1997)" (PDF). http://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic50-1-36.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ Essay prepared for "The Encyclopedia of the Arctic" by Jonathan M. Karpoff. (DOC format) HMS Resolute, itself, also had to be abandoned in the ice on that journey, although it was later found again, and became quite famous.

- ↑ A.P. "Canadian Team Finds Abandoned 19th Century Ship" NPR, 28 July 2010. Retrieved on 2010-7-29.

- ↑ John Rae—Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

- ↑ Knud Johan Victor Rasmussen, biography by Sam Alley. Minnesota State University, Mankato.

- ↑ Canada at War: THE ARCTIC: Northwest Passage, 1944, [[Time (magazine)|]] Oct. 30, 1944

- ↑ Willy de Roos' big journey at the CBC archives

- ↑ "Stricken Antarctic ship evacuated". BBC News. November 24, 2007. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/7108835.stm#graphic. Retrieved 2007-11-28.

- ↑ CBC, November 2, 1988

- ↑ Cruising, London, Summer 1992, p 35

- ↑ Northabout

- ↑ Norwegian Blue Sails the Northwest Passage

- ↑ "The North-West Passage by Sailboat". Sébastien Roubinet. http://www.babouche-expe.eu/home.html. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ↑ Nathan VanderKlippe. Northwest Passage gets political name change, CanWest News Services, Ottawa Citizen, April 9, 2006.

- ↑ Climate Change and Canadian Sovereignty in the Northwest Passage

- ↑ The Northwest Passage Thawed

- ↑ UNCLOS part III, STRAITS USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Relations With the United States from the Library of Parliament—Canadian Arctic Sovereignty

- ↑ Dave Ozeck, Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Atlantic Fleet Public Affairs. "USS Charlotte Achieves Milestone During Under-Ice Transit". http://www.navy.mil/search/display.asp?story_id=21223. Retrieved 2007-10-25.

- ↑ Most of the activities involving American submarines (including their current and past positions and courses) are classified, so therefore under that policy the U.S. Navy has declined to reveal which route(s) the Charlotte took to reach and return from the Pole.

- ↑ "Northwest Passage Gets Political Name Change". http://www.canada.com/edmontonjournal/news/story.html?id=6d4815ac-4fdb-4cf3-a8a6-4225a8bd08df&k=73925. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ↑ "Arctic Trek Shows Canada's Sovereignty". http://www.arcticnet-ulaval.ca/index.php?fa=News.showNews&home=4&menu=55&sub=1&id=128. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ↑ Dispute Over NW Passage Revived from The Washington Post

- ↑ "Prime Minister Stephen Harper announces new Arctic offshore patrol ships". Reuters. July 9, 2007. http://www.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idUSN0929956620070709. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ↑ Hugo Miller (July 10, 2007). "U.S. Bolsters Arctic Presence to Aid Commercial Ships (Update1)". Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601082&sid=aK9JSBhBiJMg&refer=canada. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ↑ John N. Harris. "The Last Viking: West by North West". http://www.spirasolaris.ca/sbb4g1bv.html. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ↑ "Arctic Marine Transport Workshop September 2004" (PDF). http://www.arctic.gov/files/AMTW_book.pdf. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ↑ Globe and Mail "Tripping through the Northwest Passage"

- ↑ Andrea Thompson, Extra Sunshine Blamed for Part of Arctic Meltdown Foxnews, Friday, December 14, 2007

- ↑ Meet your Nunavut Carrier

- ↑ 1st commercial ship sails through Northwest Passage

- ↑ NTCL

- ↑ Ports served

References

- Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole, 1818–1909. New York: Viking, 1988. ISBN 0670824917

- Day, Alan Edwin. Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Passage. Historical dictionaries of discovery and exploration, no. 3. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press, 2006. ISBN 0810854864

- Griffiths, Franklyn. Politics of the Northwest Passage. Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1987. ISBN 0773506136

- Waterman, Jonathan. Arctic Crossing A Journey Through the Northwest Passage and Inuit Culture. New York: Knopf, 2001. ISBN 0375404090

- Williams, Glyndwr. Voyages of Delusion The Quest for the Northwest Passage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 0300098669

External links

- Russia's Deep-Sea Flag-Planting at North Pole Strikes a Chill... - Washington Post

- Russia plants flag staking claim to Arctic region - CBC World

- A new race for the North Pole Russia plants flag, Canada sends troops World Socialist Web

- Canada to strengthen Arctic claim - BBC News

- CTV.ca Arctic sovereignty an important issue: Harper

- Cold Wars in the Arctic: Canada Takes on Russia in Race - DerSpeigel...

- Canada Raises Stakes In Battle To Claim The Arctic - GlobalSecurity.org

- Arctic Meltdown: The Economic and Security Implications of Global Warming - Foreign Affairs, Council on Foreign Affairs

- Arctic region likely to become the center of World War III - Pravda

- Irish Expedition completes the elusive Northwest Passage

- Arctic Passage at PBS' Nova site has articles, photographs and maps about the Northwest Passage, particularly the 1845 Franklin and 1903 Amundsen expeditions

- 'The Great Game in a cold climate'

- Mission to Utjulik

- The Voyage of the Manhattan

- Canada considers the Northwest Passage its internal waters, but the United States insists it is an international strait.

- Information Memorandum for Mr. Kissinger—The White House 1970

- CBC Digital Archives—Breaking the Ice: Canada and the Northwest Passage

- Nova Dania: Quest for the NW Passage—New England Antiquities Research Association Vol. 39 #2

- An article on the Northwest Passage from The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Virtual exhibit of documents about arctic exploration "Frozen Ocean: Search for the North-west Passage"

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||